Laying the groundwork for sustainable architecture

How does Enabel promote sustainable architecture in its partner countries? Two architects tell us more about their work in Rwanda and Burundi. Elodie Deprez and Karine Guillevic work on different projects in different countries. There is, however, a common denominator to their action: promoting sustainable architecture and taking concrete steps to widen its appeal.

Elodie Deprez is based in Rwanda, and Karine Guillevic in Burundi. While Elodie is participating in several construction projects, Karine is providing expertise on education projects dedicated to training aspiring young professionals in technical jobs. Despite these differences, both are working to make sustainable architecture more widespread in their respective countries.

No such thing as a “typical day”

Both Elodie and Karine enjoy the variety of their work. As a junior expert in sustainable architecture for the Urban Economic Development Initiative, Elodie can’t really say there are “typical days” in her work. “I’m working on infrastructure development, but also on private sector development, which means our projects are varied, the focus can be on roads, handcraft centres, local markets, and we are even constructing a youth centre.”

“I work with consultants and Rwandan companies on these different projects, but also on creating policies around circular economy, supporting companies in buying technology and supporting them towards a circular economy process. Besides, we are working in three different districts, so there is a lot of travelling to meet people on the different sites. This is also what I find exciting about this project: there are so many activities, and there is always room to create more.”

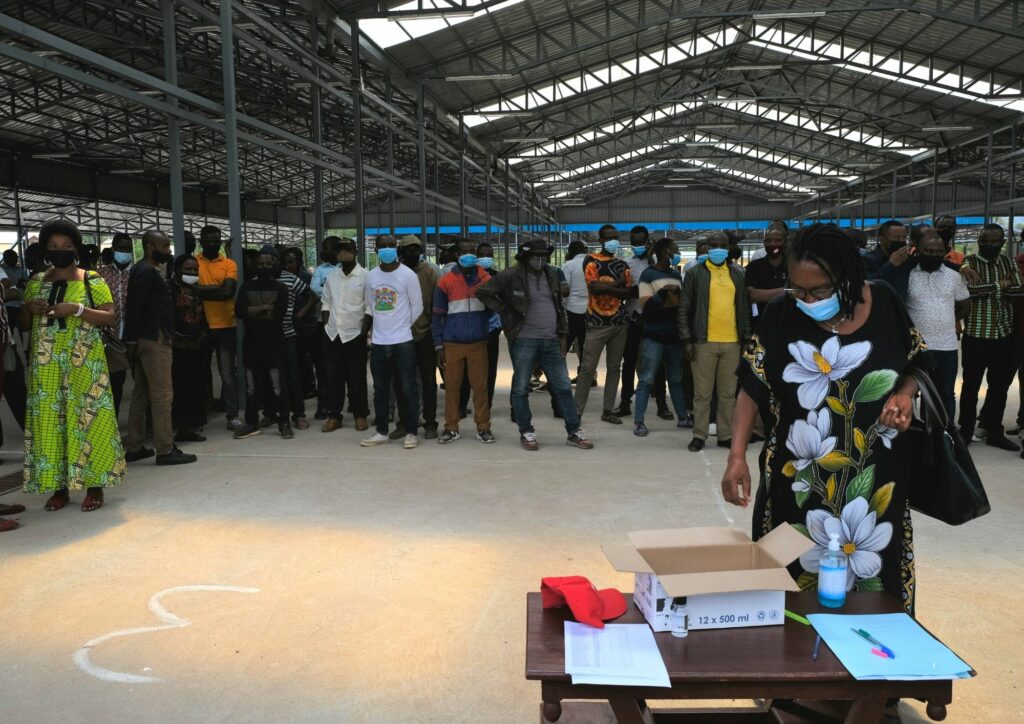

As for Karine, she works as an international architecture expert for a project that aims to answer Burundi’s needs in terms of infrastructure and equipment for vocational training centres. “We have many activities that all revolve around that objective. What I really appreciate is that, alongside the ‘classical’ approach of working with construction companies, we have started to organise ‘construction site schools’, construction sites that hire freshly graduated students. It gives them the opportunity to acquire a first professional experience while being coached by teachers and by experienced construction workers.”

We started to organise ‘construction site schools’, construction sites that hire freshly graduated students. It gives them the opportunity to acquire a first professional experience while being coached by teachers and by experienced construction workers.”

Karine Guillevic- Architecture expert in Burundi

Promoting a holistic approach

Advocating for sustainable architecture requires some persuasion, in Rwanda as well as in Burundi. “The default mindset for architects is to use concrete for the structure of the building. But concrete is an imported material and uses up a lot of energy to be produced,” explains Elodie. “Which is why we are pushing for local materials, such as stone, bamboo, agricultural byproducts and perforated brick.”

Perforated brick is a new type of construction brick, it’s based on traditional materials, and can replace reinforced concrete for the load-bearing structure of a building. As it is locally produced in Burundi and Rwanda, perforated brick also contributes to the economy by allowing local producers to grow.

Both Karine and Elodie work in cooperation with SKAT PROECCO, an organisation that helps promote perforated brick by providing technical expertise and training to architects and construction companies. “They are also providing training to the bricklayers who will work on the construction,” Karine adds. “And that includes not only the workers on regular construction sites, but our freshly graduated bricklayers who are working on our construction site schools.”

In pictures: Showing the evolution from construction site to Multimedia Resource Centres accessible for young people in Burundi.

“We consider cities as living beings, with a complex ecosystem that needs to create space for citizens, the environment and the private sector. There should be room for all of them to thrive.”

Elodie Deprez- Architecture junior expert in Rwanda

Thinking beyond projects

This training is a critical part of the sustainable architecture project. “We are working on creating a virtuous cycle,” Karine explains. “It is not enough to train architects to incorporate perforated bricks in their projects. We need to make sure there are enough qualified workers who have experience with that material, so construction companies can hire them. This way, we can create a virtuous circle: completed buildings serve as proof of concept for developers, architects. Construction companies build up experience working with these materials, and so do workers. In other words, all the stakeholders in the construction ecosystem are included in the drive towards using sustainable materials and therefore support each other.”

Besides promoting sustainable architecture, using local materials also has other implications. Using materials that have a strong link to local building traditions makes maintenance easier and less expensive. It also promotes social inclusion, by providing work to the younger generation. “It matters a lot in countries where the population is especially young. And it also helps to make sure the youth will engage in activities that are better suited to the environmental challenges we are now facing,” says Elodie.

Elodie continues: “We consider cities as living beings, with a complex ecosystem that needs to create space for citizens, the environment and the private sector. There should be room for all of them to thrive.”

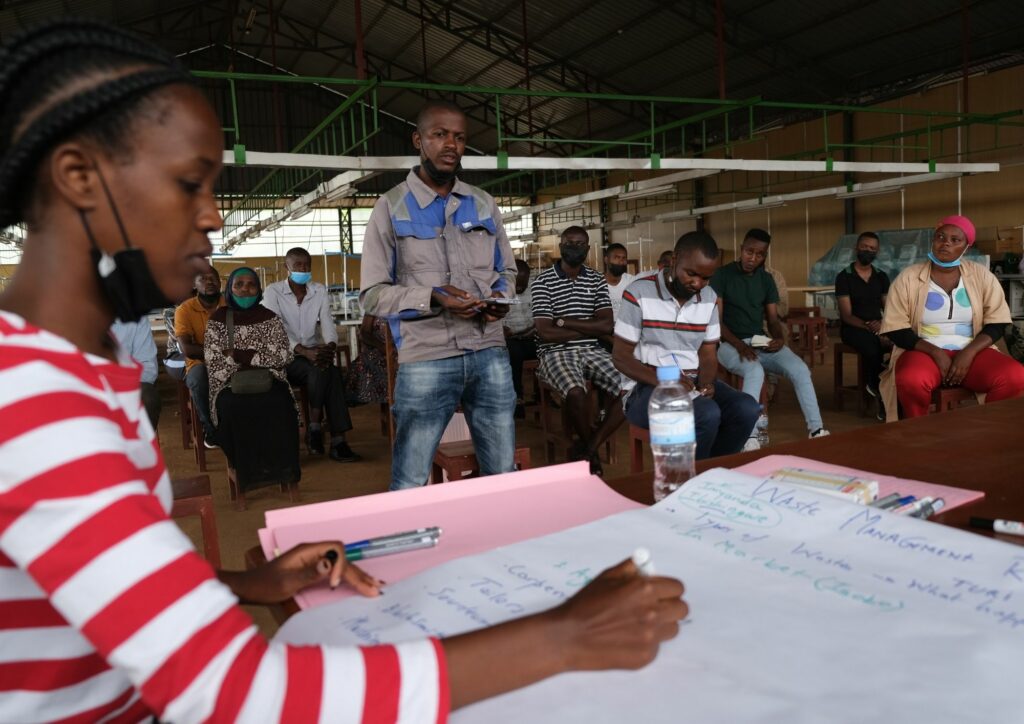

In pictures: Citizens in Rwanda sharing their ideas on urban development. Designing public spaces that match the needs of potential users.

Architecture for the people

Sustainable architecture is more than just promoting sustainable materials. “It also means working with communities,” Elodie explains. “In Rwanda, in the recent past, a lot of modern buildings have been built that end up empty, because they don’t really answer the needs of their potential users. Integrating citizens in each project allows architects to gather their input and incorporate it in the design.”

Karine agrees whole-heartedly. “Usually, people are very open and want to contribute: they have ideas to share as well as useful information. For example, if you want to build a very big market, it will exclude the small shopkeepers that are part of the community. Finding ways to integrate their needs into the project will help make sure this new market gets wide acceptance.”

Corona, its strict regulations, and time restraints, created a challenge for the organisation of community gatherings. However, it is never too late to include the community and create small-scale projects around the constructions that will include their ideas and boost ownership and pride. As Elodie illustrates with an example “besides a market, you can have community gardens, offer support in the co-designing of smaller shops connected to the bigger infrastructure, help in the integration of waste management, include local artists or youth and so on.”

This leads Karine to insist on the social role of architecture. “When you think about architecture, you tend to think it’s about aesthetics. But sustainable architecture goes well beyond that: its role is to boost the dignity of the community through active participation. By involving them in the project, you end up with buildings that are better conceived and tailored to the needs of citizens. It creates a sense of ownership and pride.”