“The best Great Green Wall? Where people live in harmony with the environment”

What progress has been made on the Great Green Wall in the Sahel? This green strip, 15 km wide and 8,000 km long, is intended to halt the desertification of the Sahel, a vast semi-arid region between the Sahara and the sub-Saharan tropical savannas. “The project has come a long way since the initial idea. Just planting trees is not enough,” says Oblé Neya, the coordinator of Enabel’s Climate programme in West Africa.

First of all, how did the Great Green Wall initiative come about?

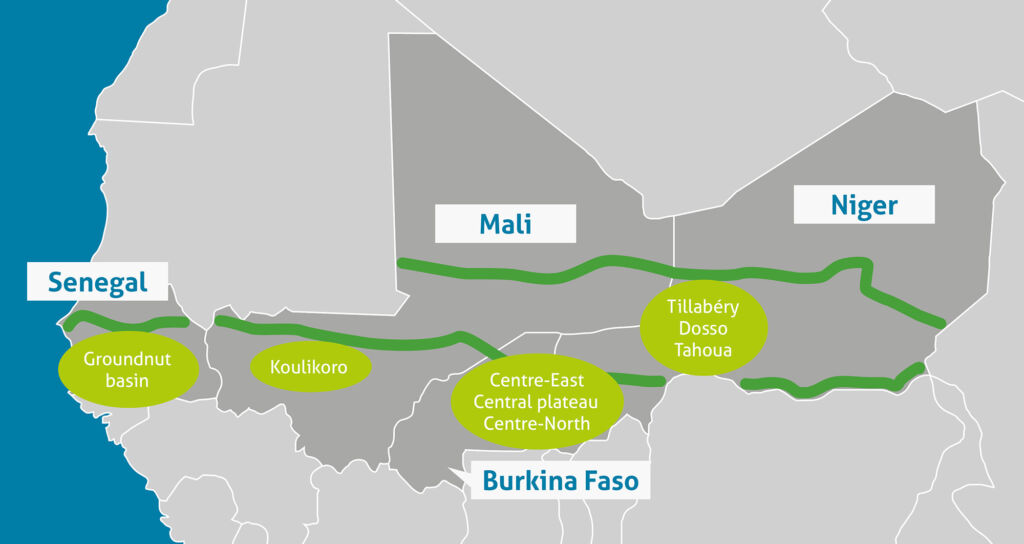

The initiative was launched twenty years ago at an African Union summit. It really got off the ground in 2007. Today, 11 countries are involved, from Senegal in the west to Djibouti in the east. Enabel’s support began in 2022; it is focused on 4 of the 11 countries: Senegal, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso.

According to estimates made in September 2021, 15 % of the Wall has been completed to date.But in reality, it does not seem easy to estimate the state of progress of the Great Green Wall?

This is to be expected, because the initiative’s approach and indicators have evolved considerably since its inception. Initially, the idea was essentially to create a gigantic green corridor by planting trees, and this idea has remained in many people’s minds. But since then, we have realised that just planting trees is not enough. Focusing on a single objective, without considering the rest, is not the way to address a challenge as complex as the fight against desertification. This is why the approach was fundamentally revised in 2013.

What has changed since 2013?

The initial idea – a large continuous green strip – turned out to be too simplistic, even though it provides for a beautiful image. We have moved on to much more localised and comprehensive projects: Today, the aim is to create a multitude of green basins in the Sahel region.

As for the approach, it’s a comprehensive one. Because, if we want to combat desertification, we must first ask ourselves why a region is becoming desertified. It’s not just a question of climate, but also of integrated water and land management, adaptation and participatory governance, among many other factors.

It makes no sense to run a ‘climate change’ project, an ‘agriculture/livestock’ project and a ‘biodiversity’ project in parallel. All these aspects need to be integrated into a single, comprehensive and integrated project, based on the well-being of the local population.

How does Enabel select villages or areas it wants to transform into green basins?

The first criterion is obviously the geographical location, which must be within the area covered by the Great Green Wall. Secondly, we need to take synergies into account: we prefer to work in regions where we are already active, where projects are already underway. It is more effective and it is consistent with the approach I have just outlined. Finally, we are targeting areas that are most affected by drought and land degradation, with significant natural resource management problems.

How do you convince local people of the merits of an initiative like this?

If a project doesn’t work, it is because it probably did not meet the needs – at least those of the local communities, which are essential partners. We cannot launch a comprehensive project without taking into account the concrete needs of local populations.

To convince them, they first need to see both short- and long-term benefits. That’s why, in each village, we start with participatory planning. In practical terms, we identify local opportunities: natural resources, water infrastructure, land to be developed, local practices and activities, such as pastoralism. Then the communities tell us about their needs, their problems and the solutions they have already tested or which they think would be appropriate to solve these problems.

In many cases, managing natural resources is already a source of conflict in these communities. So, when you are planning to restore land, you need to ask yourself from the outset: What are you going to do with the restored land? What will it be used for and who will benefit from it? Will it be used for farming, as fields, or for grazing livestock? Or do we leave it as it is, as land serving to preserve biodiversity? It is a decision that has to be taken collectively. Otherwise, we create more problems than we solve.

Enabel is keen to ensure that the project also benefits women and young people. How can you be sure of this?

We work on the basis of Calls for Proposals, to which civil society organisations and NGOs respond. The projects proposed must always have a component dedicated to economic opportunities for young people and women. The problem is well known: access to land and resources is very complicated for these two groups.

The approach is often to involve them in the process of restoring degraded land – land which is considered useless and which therefore no-one claims. As long as women and young people are actively involved in this work of reclaiming the land, it gives them the legitimacy to participate in the decision-making process on how this land will be used in the future.

In fact, women and young people are key partners in this type of project. In many villages, the men are often absent because of their activities. Young people and women lead a more sedentary lifestyle. Of course, they already have a lot of work to do, but they are still the ones who are more available.

Let us go from the local to the international level. Are the countries directly involved in the Great Green Wall initiative cooperating sufficiently?

This is one of the major challenges, but also one of its objectives in its own right, because we believe that when countries work together on joint projects, it is a factor for peace in a region.

But it has to be said that there is still a long way to go. A Pan-African Agency for the Great Green Wall was set up at the time, but it has to be said that it is not actively playing its role – possibly due to a lack of resources! As a result, each country looks for its own partners and the tools and approaches are not always the same on one side of a border or on the other, which is not ideal because nature has no borders.

My role at Enabel is precisely to facilitate the coordination of efforts in the 4 countries with which we are working in support of the Great Green Wall initiative. Sharing experiences is essential in a project like this: to capitalise on what has been learned, avoid repeating the same mistakes and share successful recipes.

How do you see the future of the Great Green Wall?

Through the Enabel project, we aim to restore 10,000 ha of land in each of the 4 partner countries, i.e. a total of 40,000 ha. The second phase will involve finding new functions for the reclaimed land – a function that helps the environment and creates opportunities for women and young people.

The project started in 2022 and we already want to see tangible results by 2025. But setting a strict deadline for a project like this is unrealistic. The success of an environmental project is really measured in the long term. For me, best Great Green Wall, is where people live in harmony with the environment.